My feet have hardly touched the ground since January, when Hearts and Minds was published. After a launch and lecture at the Women’s Library (LSE), I started on a round of talks and media appearances – 53 events at the last count – which won’t calm down till November. Perhaps naively, I had no idea how widespread publicity about the suffrage centenary would be. I have never been so much in demand as a speaker, and I love it. People ask if I get nervous. I don’t, because I’m used to public speaking and hugely enjoy interacting with audiences. It’s one of the best perks of my job as a writer. But there have been some unforeseen challenges. One of these was wondering how to respond live on air when a radio host introduced me with great aplomb as a historian not of suffragists, but ‘suffrage gits.’

Another was the visual media’s obsession with foundation, concealer, mascara and rouge. On 6 February, the very day of the centenary commemorating (some) women getting the vote in 1918, I had four TV things going on, with different companies. And each time I arrived at the relevant studio, I was greeted by bright and breezy make-up people who whisked me into their spangly lairs with tutting and rolling of eyes. “Ooooh, I think we need to colour you up a bit,” said the first one. She sealed my face completely in various products and made my eyelashes so bushy they scraped the inside of my glasses. Fine, OK, I thought. If this is what it takes.

Woman at her Toilette, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec (WikiArt.org)

The lady at my next stop took one look at me (by now as heavily made-up as I have ever been) and sucked in her breath. “Oh dear, Jane. Time for a bit of magic.” On went as much again. It was becoming difficult to smile. A quick taxi-ride took me to a lunchtime talk at a girls’ school where I apologised, mortified, for my bizarre appearance (though someone said I looked ten years younger. Only problem was I’d never met them before. How old did they think I was?). Then I dashed to studio number three. “Hi, Jane. Ah. We’d just like to treat you to a light going-over, if that’s OK? I think it’ll help.”

By now I felt inhuman. Greasy black smuts fluttered from my eyes every time I blinked, and my lips were not where I had last left them. I shrugged. What the hell. One must suffer for one’s art. The last engagement was back at the studio where I’d started. At least they wouldn’t try to tart me up any more. But my make-up artist had left for the day. The new one took one look at me, and…

It took me a good twenty minutes to get everything off that night. I have new respect for television presenters who go through this every day. Mind you, I’m a little more blasé now, and have more confidence; I just ask for the very minimum to make me look as though I’m alive (being Celtic, I’m naturally pale, and when I’m tired, turn a beguiling shade of battleship-grey). I’m not there as me, anyway; I’m there to talk about the people in my book.

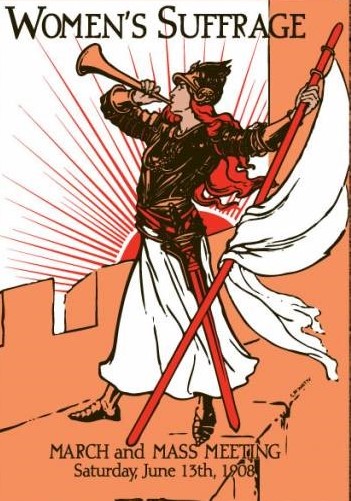

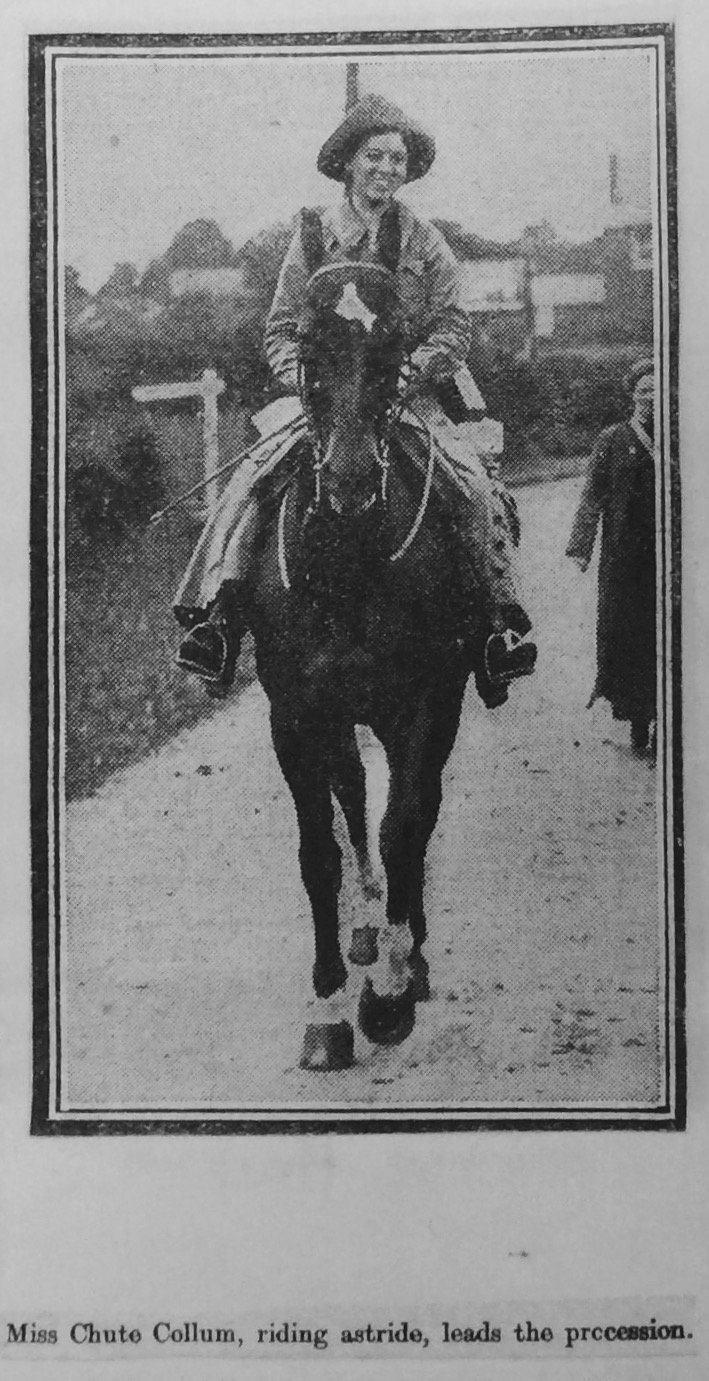

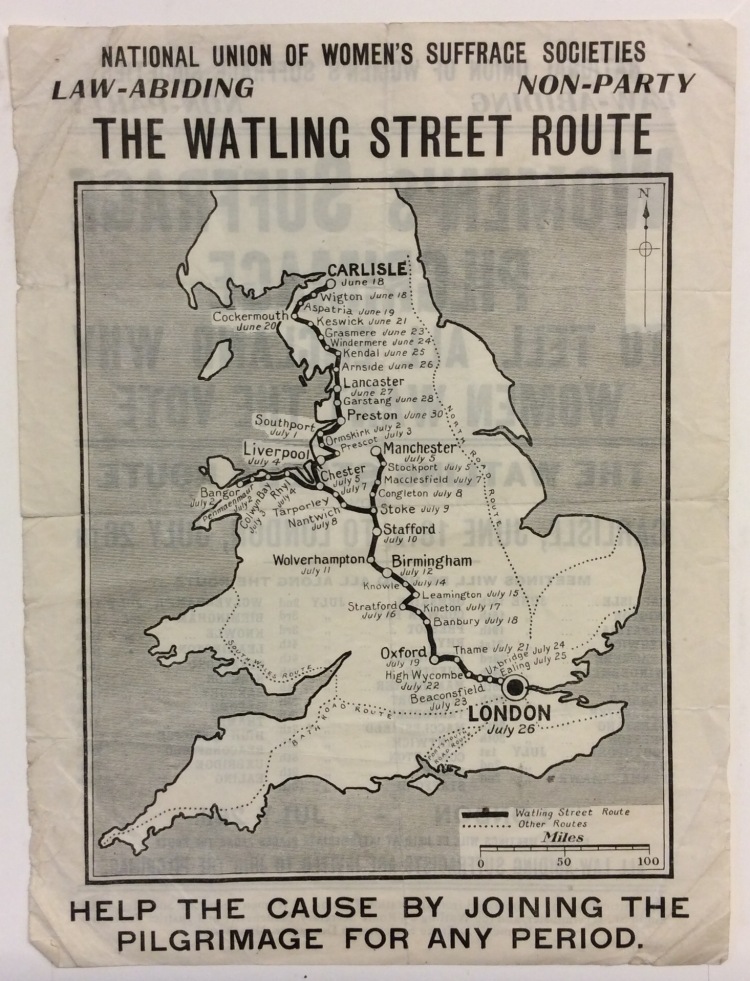

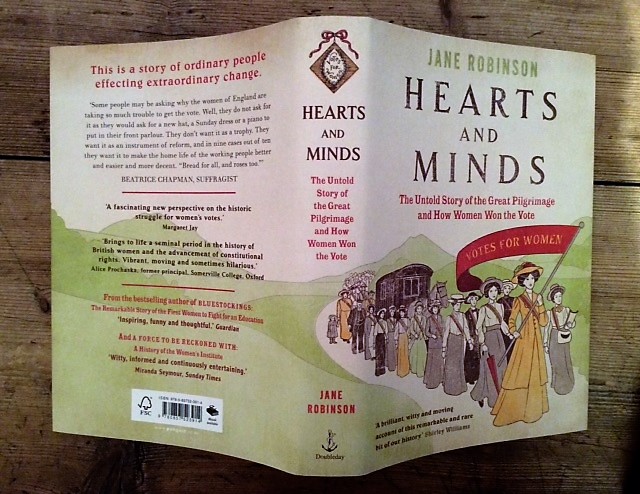

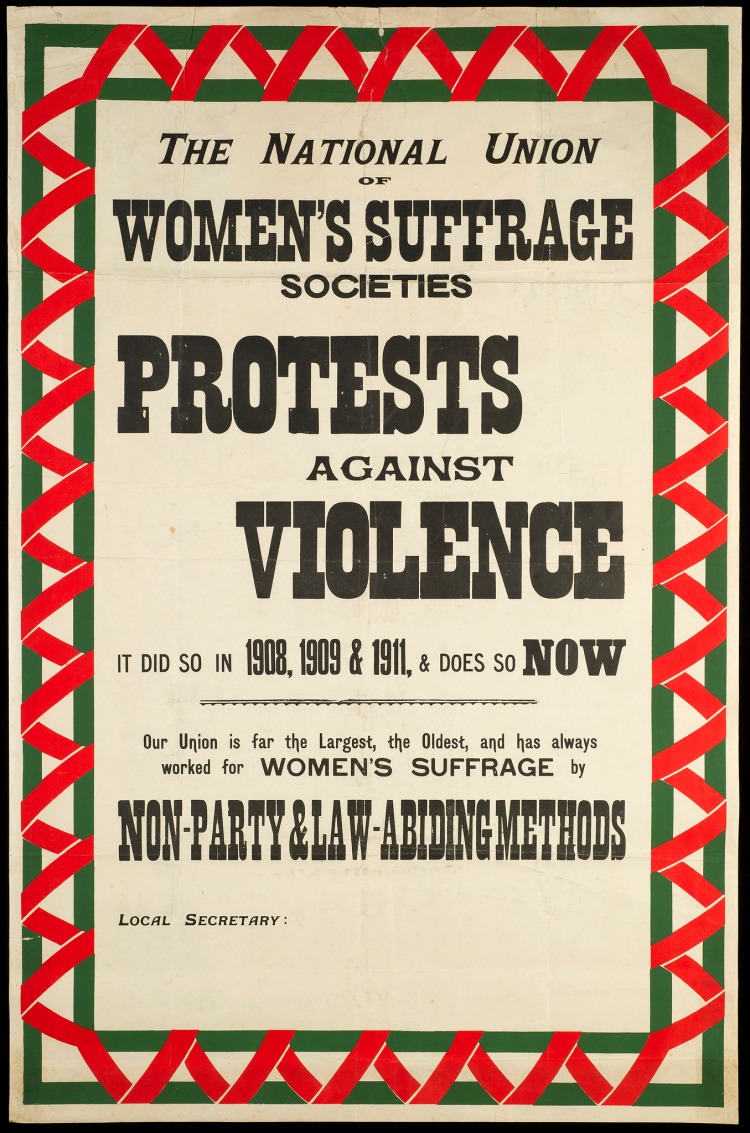

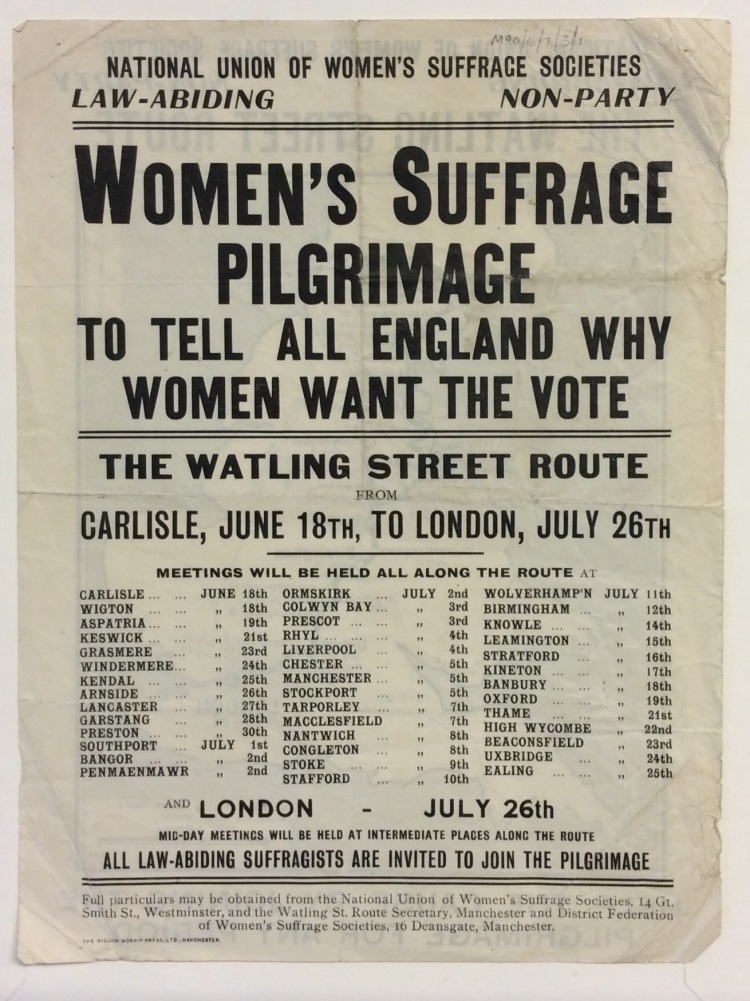

And that’s been the greatest pleasure of the last few exciting weeks: the opportunity to introduce so many readers and listeners to the women’s march of 1913 – the Great Suffrage Pilgrimage – and to an alternative view of the centenary not exclusively involving suffragettes, but the non-militant majority, the suffragists. Theirs is such a live story; about #metoo, the gender pay gap, women’s activism and grass-roots solidarity; about having a voice and using it not so much to claim our own individual rights as to make the world a more equitable and responsible place for us all. Every time I tell their story, as I whisk from Glasgow to Brighton, from the Broads to the Dales, I am inspired anew by their courage and cheerful pragmatism.

Pilgrims at Headington, Oxford (Duke University)

Here am I bleating about life on the road – too much make-up, or a late plane, or a projector not working properly. How would I do, I wonder, if I had to walk for six weeks on mud tracks through an English summer to make my point, in boots swarming with blisters with people throwing rocks at me and constantly being told I was an hysterical air-head with no more right to a vote than a lunatic or a criminal?

Maybe I should try it, and see.

Now that I have finished Hearts and Minds: Suffragists, Suffragettes and How Women Won the Vote (out next January, https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/1111210/hearts-and-minds/) I realise that similar questions arise in connection with enfranchising women. By the time the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act was passed in December 1919, a minority of women were equipped with academic qualifications and with a vote – but what could they do with them?

Now that I have finished Hearts and Minds: Suffragists, Suffragettes and How Women Won the Vote (out next January, https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/1111210/hearts-and-minds/) I realise that similar questions arise in connection with enfranchising women. By the time the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act was passed in December 1919, a minority of women were equipped with academic qualifications and with a vote – but what could they do with them? Enid Starkie (1897-1970) was a fantastically eccentric academic (right, ex.

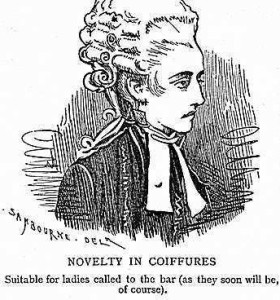

Enid Starkie (1897-1970) was a fantastically eccentric academic (right, ex.  Barrister Helena Normanton (1882-1957) was the first woman to prosecute in a murder case; Irish architect Eileen Gray (1878-1976) inspired Le Corbusier… and so on.

Barrister Helena Normanton (1882-1957) was the first woman to prosecute in a murder case; Irish architect Eileen Gray (1878-1976) inspired Le Corbusier… and so on.

(Oldham Local Studies and Archives)

(Oldham Local Studies and Archives)